Indigenous History in La Plata County

Indigenous people are essential in this region’s story, and it is crucial to understand and acknowledge their importance. The history of Indigenous people is often ignored, dismissed, or misrepresented in mainstream narratives, leading to a distorted view of their experiences and their contributions to society.

Learning Indigenous history helps us appreciate and respect cultural diversity, understand the impact of colonization, study Indigenous land stewardship practices, promote social justice and equality, and enhance education.

Exclusion of Indigenous History

One of the main reasons that Indigenous history has been excluded in the United States is the pervasive idea of a "white Anglo-Saxon Protestant" culture that has dominated American history. This narrative has tended to overlook the experiences of people from other ethnic and racial groups, including Hispanics, African Americans, and Indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples' systematic exclusion from academic institutions and historical research has contributed to the erasure of Indigenous history. Indigenous peoples were also excluded from positions of power and decision-making, making it difficult for their perspectives and experiences to be included in mainstream historical narratives.

The lack of written records and documentation in Indigenous cultures has also made it difficult for their histories to be preserved and transmitted to future generations.

Even more problematically, early archaeologists in the 18th and 19th centuries tended to discount the idea that Indigenous people had any connection to the creation of monumental architecture and permanent stone dwellings. Instead, theories unbound by fact sought to connect the ruins to known civilizations like the Egyptians, Hindus, or Aztecs. Thus, many of the local Ancestral Puebloan archaeological sites were named with the presumption that they were connected to the Aztecs of Mesoamerica. Perhaps worst was the popular idea that North America had been home to a “vanished white race” responsible for any notable discovered structures.

These ideas and notions harmed contemporary Indigenous people and made them villains in a story of civilization's downfall, used to justify ethnic cleansing and violence. The study of Indigenous peoples was linked to government policies of cultural genocide, and even archeological research was often used to support racist theories. Exploiting archeological sites for tourism was expected, and there was little distinction between “pothunting” and professional archaeological digs.

Indigenous oral traditions and modern archaeology have had a hand in correcting the public’s knowledge about Indigenous history before colonization. These oral traditions, often dismissed in Euro-centric circles as unreliable sources of historical information, encompass many stories, songs, dances, and other forms of historical knowledge passed down orally from generation to generation. Abundant archaeological evidence also tells the story of strong, independent nations that continue to thrive today. Together, these nuanced historical approaches paint a rich, truthful picture of flourishing societies in Precontact America.

8,000 BCE-1400s

The Ancestral Puebloans

Archeological evidence suggests hunter-gathering people in Western Colorado as far back as 8,000 BCE, followed by Ancestral Puebloan peoples who settled there. The Ancestral Puebloans lived in the area from roughly 200 AD to 1300 AD and are known for their remarkable achievements in architecture, art, agriculture, and engineering.

One of the most impressive feats of the Ancestral Puebloan people was their construction of large, multi-story stone and adobe buildings often built into cliffs' sides. These structures, known as cliff dwellings, were both functional and beautiful, providing shelter and protection from the elements while also showcasing the artistic and architectural skills of the people who built them. The Ancestral Puebloans were also known for their creative and cultural achievements, including pottery, weaving, and intricate rock art.

Migration of Ancestral Puebloans

By 1350 CE, the Puebloan people migrated south, and Navajo and Ute's peoples arrived. The dating on this is contested, precisely the framing of other peoples as only recently “arrived.” It is best not to frame the shift in Ancestral Puebloan civilization as a “collapse,” “fall,” “doom,” or other dramatic narratives. These were common ways of contextualizing the end of a period of centralized, permanent urban settlement. But they imply a disastrous calamity and the disappearance of an entire people, erasing the connection to contemporary descendants.

The most common theory is that an extended period of drought caused this shift, although how quickly it occurred and under what other circumstances remains debated.

Today, only the Ute people under the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and the Southern Ute Indian Tribe still retain reservations in Colorado. However, it is worth noting that several Indigenous nations have ancestral ties to these lands.

1500-1600s

Contact and Spanish Conquest

Following Columbus’ conquest in 1492, the Spanish Empire arrived in the Southwest 1530s after dispatching an expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who died in 1528. The first contact between the Ute people and the Spanish occurred in 1540 when the Spanish explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado later led an expedition through the Southwest in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Gold. The Ute people established a trade relationship with the Spanish, exchanging goods for European tools and weapons.

Spanish records note the Ute bands north of Santa Fe, Taos, and Abiquiu. The historical range of the Ute people was estimated to be over 130,000 square miles at the time. This large territory, like many others belonging to Indigenous nations, would shrink as the first wave of colonization began.

Though seemingly innocent, these conquests were the pretext for establishing colonial settlements and garrisons in the Americas. Coronado's expedition encountered several Ute bands, and despite initial friendly relations, the Utes soon became hostile when they realized the Spanish were not leaving.

These conquests, conducted primarily on horseback, preceded Spanish settlement of the same area. The spread of horses into Ute culture via Great Plains people occurred in the 1580s, spurring the adoption of new technology and ways of life. This included intensified raids and counter-raids with neighboring peoples and facilitated participation in the slave trade with the Spanish as both captives and sellers of captives.

In 1637, Ute captives in Santa Fe escaped with their lives on Spanish horses. This left the border regions of the Spanish empire in the Four Corners region more sparsely settled with Hispanic peoples. As time passed, these interactions set the stage for Ute's relations with the Spanish.

1700s

Relations with Spanish Colonizers

Tensions between the Ute and the Spanish escalated throughout the 1700s as the Spanish attempted to exert greater control over the region. Spanish soldiers often clashed with Ute warriors, leading to violence and bloodshed on both sides, like the Ute raids on Abiquiu, which led to its temporary abandonment in 1730.

Additionally, the Spanish brought diseases to which the Ute had no immunity, leading to devastating epidemics that decimated Ute populations. Spanish and Ute's relations improved in the 1760s, sparking more interaction and trade.

Despite these challenges, the Ute maintained their independence and resisted Spanish attempts to control their territory. They used their knowledge of the land and their military prowess to repel Spanish attacks and maintain their sovereignty.

Timpanogos Partnership with the Spanish

With aid from Indigenous guides, the Spanish explored north into southwestern Colorado. Juan Antonio Maria de Rivera traveled from Santa Fe to Gunnison in 1765. Later, Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante set out in 1776 to find an overland route from Santa Fe to Monterey, California. Their guides were Timpanogos, a close relation to the Ute and Shoshone peoples, and their route became the basis for the Spanish Trail. However, these partnerships would be shortlived with the establishment of the United States.

1800s

The Emergence of the United States

The early 1800s saw a significant shift in the power structures in the region as the United States steadily gained supremacy in the region. In the 1820s, Mexico secured its independence from Spain. After gaining independence from Spain, Mexico continued to establish settlements further north. In the 1840s, New Mexico settlements further encroached on Indigenous lands as the Mexican-American war erupted.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. As a result of the war, Mexico turned over control of the New Mexico and Colorado Territories to the United States, bringing soldiers, settlers, and railroads further west. The treaty gave property rights to Mexican citizens north of the border but not Indigenous inhabitants.

The Utes proposed a treaty with the United States to preserve their shrinking territories in 1822, but the first treaty was not signed until 1849. The Ute tribe initially had friendly relations with the United States government, as they were seen as an essential ally in the government's efforts to expand westward. Seeking to improve their relations with the United States, the Utes allied with the U.S. to fight the Navajo in 1860. During this time, several agencies for Ute bands were established in the early 1860s, though only some remained in those locations permanently.

Discovery of Precious Metals and Loss of Ute lands

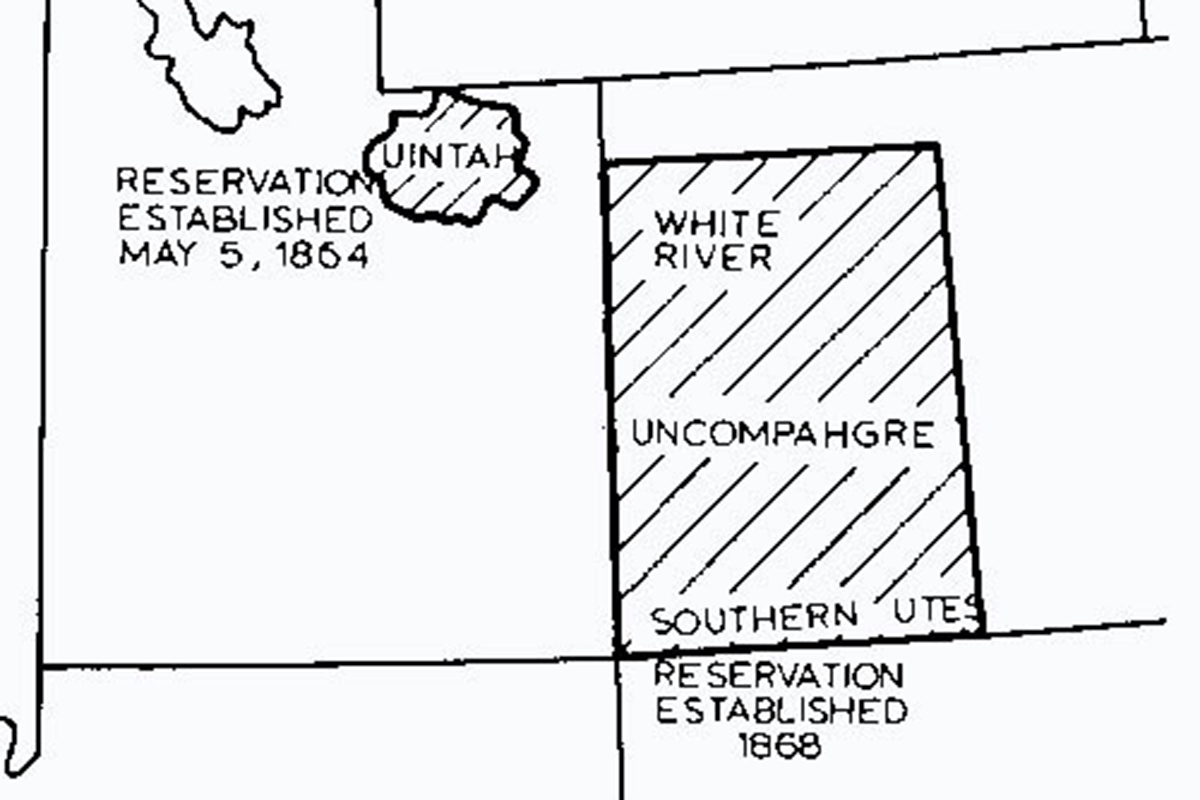

An 1863 treaty effort included Ouray, an Uncompahgre leader known for his skills as a peace negotiator. In 1868, Ouray was selected as the principal chief for treaty negotiations that would affect all Ute bands and remove them to reservations compromising the western third of the state of Colorado, dubbed the “Kit Carson” Treaty for his participation in negotiations in Washington, DC. However, in 1868 the wealth of the San Juan mountains was not yet known to the United States.

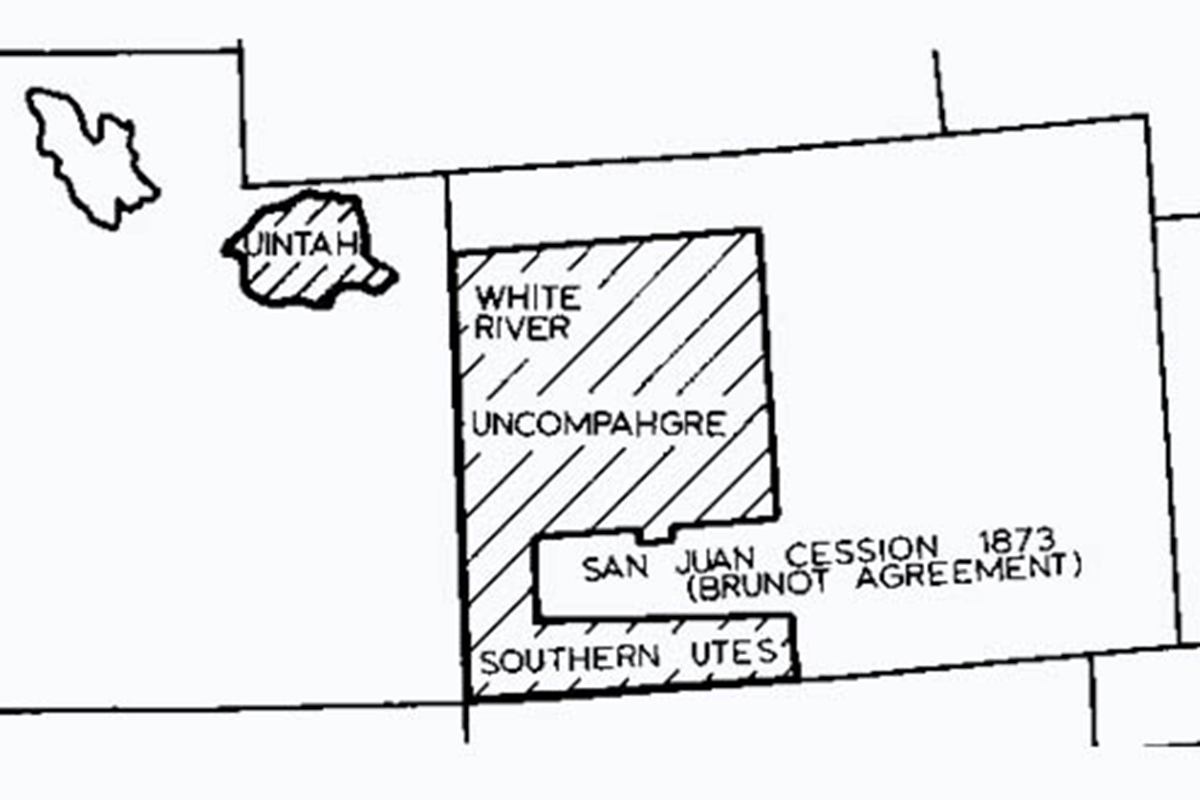

Upon discovering precious metals in the San Juan Mountains, the United States pressured the Ute bands into signing the Brunot Agreement of 1873, which cut out the mountain range from Ute lands. This would lead to the development of the mining industry in Durango and beyond. In exchange, the Ute bands would receive $25,000 annually in perpetuity and retain hunting rights in the ceded mountain lands. As a final negotiating tactic, Ouray asked for a tract of land near present Montrose for himself and his wife and a $1,000 salary. This last item proved difficult for Ouray, as other Ute people took it as proof of his betrayal.

Shortly after that, Indian agent Nathan Meeker tried to convert the White River Utes at their reservation to follow the lifestyle of sedentary farmers and Christian beliefs. After a year of tension, Meeker plowed a favored green valley used for grazing and racing Ute’s horses, threatened to withhold annuity payments, and asked that the cavalry patrol the woods to prevent the Ute people from hunting or foraging for their food. In response, the Northern Ute bands killed Meeker and his men, leading to their forced removal from Colorado to Utah.

Establishment of Fort Lewis

In the 1860s, the United States military was involved in frequent conflict with Indigenous nations in the Southwest. In response, the U.S. sought to clear Indigenous people from the land entirely—much like the British. To do this, the military established Fort Lewis, a U.S. Army post from 1878 to 1891, to conduct military operations against Indigenous nations. The presence of Fort Lewis and the need to feed and supply the soldiers there is credited with kick-starting the local agricultural economy, as it created a reachable market for surplus goods.

Fort Lewis would later be converted into a federal Indian boarding school in 1892 to serve the same genocidal purpose, albeit differently.

Federal Indian Boarding Schools

Even more problematic was the establishment of federal Indian boarding schools in the 1870s. This school system was established to assimilate Indigenous children into Anglo society with horrific results forcibly.

Half of the children at the Albuquerque Indian Boarding School, established in 1881, died in 1894. One-quarter of the children sent to Fort Lewis Indian School, established in 1892 in Hesperus, went blind. After these events, there was deep resistance from the Ute people, as well as other tribal nations, to send their children to boarding schools.

Early Durango and the Mining Boom and Bust

In 1878, a group of prospectors led by William Jackson Palmer discovered silver and gold in the Southwest region. The discovery led to a rush of people seeking their fortunes in the region, and the town of Durango was established in 1880. Durango was later incorporated into the D&RG branch lines that were constructed in 1887.

Durango’s economy was dependent on Silverton’s silver and other mines. Businesses in Durango smelted the ore and shipped out commodity products. Ample supplies of timber, coal, and clay in the region aided the growth of the small industrial town, with railroad spur lines bringing those commodities within easy reach.

After that, the mid-1890s saw warming relations between Ute peoples and Anglo settlers in Durango, with participation in fairs and events. People showed great interest in Indigenous peoples if a profit could be turned. But accepting them as permanent neighbors was an entirely different matter. The State and Federal census of 1885 showed Durangoans were native-born primarily, white, and married, with two-thirds of the white population from Great Britain and Ireland and one-third from Germany.

The tolerance from Anglo settlers was tentative at best, however. The 1893 Silver Panic, a crippling blow to Durango’s mining industry, worsened relations between the Anglo residents and the nearby tribes. During this time, David F. Day, owner and publisher of the Durango Democrat newspaper, would repeatedly call for the expulsion of all Ute peoples from Colorado. The turn of the century would see more challenges for local tribes.

1900s

The Challenges of the Early 1900s

In the early 1900s, the Indigenous population in Durango and the surrounding areas continued to face significant hurdles due to colonization and assimilation policies implemented by the United States government.

These issues were further compounded in the 1920s with the Ku Klux Klan takeover of state and local governments in Colorado, including Durango and Bayfield. Colorado had the second-highest per capita Klan membership in this era. Governor Clarence Morley, members of the state supreme court, Denver’s mayor, police chief, and others in the justice system were all Klan members in this peak of activity. In Durango and Bayfield there were Klan marches, cross burnings, and a string of arson. The KKK even threatened to burn down the convent and Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

The Great Depression was also tough on Indigenous peoples and was a compounding factor in their emigration away from the area. Selling looted Indigenous artifacts was a popular means of making money during the Great Depression. However, this was ameliorated when some jobs became available when the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) funded regional projects.

Federal Indian Policy Developments in 1934

In the 1930s, the ballooning sheep population prompted the United States government to pass the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, which attempted to quell competition over grazing public lands through regulation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) enforced this law on tribal lands and targeted Navajo sheep herds. The same policies affected the livestock of Ute Mountain Ute and the Southern Ute nations. This contributed to the shift towards cattle raising instead of sheep. With help from the CCC, wage-earning agricultural cattle jobs formed and drew members from the Navajo Nation into the area.

The United States government also passed the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which granted remaining surplus land previously taken from reservations to be restored to their tribal owners. However, Anglo settlers did not take this measure kindly, and Senator Alva B. Adams added an amendment “banning the transfer of most Colorado land to the Utes.” This quick reversal would begin many different, inconsistent eras of modern federal Indian policy.

Wartime Mining in the Durango Area

In the 1940s, wartime economies periodically revived the extraction and refining businesses. In WWII, the early Cold War, Uranium and vanadium mills significantly inflated Durango’s economy. Mill workers in Durango were not informed of the danger, though, nor were nearby residents. Many Santa Rita people who worked for the mill directly interacted with the radioactive tailings. Uranium mining to the south in Shiprock poisoned workers, many of whom were Navajo.

The Vanadium Corporation of America (VCA) leased the Smelter Mountain uranium mill in 1948 and purchased it outright in 1953. Until 1963, the mill was an important source of jobs. The Four Corners region has deposits of the mineral carnotite, an ore containing large amounts of uranium and vanadium.

Sourced within the Colorado Plateau, the VCA milled the ore on the side of Smelter Mountain on the banks of the Animas River, leaving behind a massive tailings pile estimated at 1.2 million cubic yards. Because of the secrecy inherent in the nuclear weapons program, the health risks of these tailings were not disclosed to the public or the workers involved. The danger of the tailings comes from their toxicity rather than being an immediate radioactive danger. Unfortunately, however, the choices made did little to minimize the longer-term risks of exposure.

By 1978, Durango was considered the fourth-most uranium-contaminated site in the country, leading to massive clean-up efforts in the 1980s, with over a hundred new sites discovered in 2019.

Fort Lewis College Native American Tuition Waiver under Fire

In 1971, the Fort Lewis College Native American tuition waiver became a target of budget-conscious state politicians. The release was enacted as Fort Lewis Indian School reformed into a higher education institution in 1911. State politicians argued that Colorado should not pay for out-of-state Native American student tuition. This argument was buttressed by the original legislation turning over the Fort Lewis Indian School to the State of Colorado specified that the school was in Hesperus and that by moving the college to Durango, the original agreement had been violated.

This spurred local protests by students and garnered attention in the state press. Indigenous students took to the Old Fort campus in Hesperus to occupy it, demanding that the lands under the Old Fort be returned and that the tuition waiver be reinstated. The Old Fort was occupied from May through early October 1971, and the state legislature reinstated the tuition waiver shortly after that.

Economic Boom for Tribes in Durango

In the latter half of the 20th century, tribes in the area would become an economic powerhouse in the region through Indian gaming and oil projects.

After decades of being required to lease out mineral and energy rights to outside companies under the 1938 Omnibus Tribal Leasing Act, the 1970s and 1980s saw substantial changes to the ability of tribes to realize a more significant portion of their underground wealth. In 1975, the two Colorado Ute tribes joined to form the Council of Energy Resource Tribes (CERT), which welcomed 41 other tribes by 1988. Members of CERT shared scientific data, technical information, and political connections to position themselves in the market better. The Indian Mineral Development Act of 1982 authorized tribes to conduct their own negotiations. This led the way to the Southern Ute Tribe gaining “complete ownership of oil or gas wells” and the creation in 1992 of the Red Willow Production Company.

The 1990s also saw the opening of tribal gaming and gambling operations. The Sky Ute Lodge and Casino proved highly successful in its first year of operation, yielding revenues of twice the amount that had been forecast for the new venture.

Indigenous nations in Durango today

Contemporary Indigenous peoples in Durango are resilient above all else. Despite significant historical and ongoing challenges, they have maintained their cultural heritage and identities. They also have a unique and valuable perspective essential to our understanding of today's world.

With a deep connection to the land and traditional practices of managing natural resources, Indigenous knowledge is invaluable for sustainable development in Durango. They have an understanding of the natural world that is rooted in respect for the interconnectedness of all living things. This knowledge is increasingly recognized as a critical component of conservation efforts and efforts to combat climate change—which continues to threaten our mountain community.

The tribes in this region have a strong tradition of agriculture and have been instrumental in preserving the natural resources in the region. They also operate several successful businesses that generate revenue for the local economy, including casinos and gas and oil production companies, providing jobs and economic benefits to the tribal and local communities. They have also been strong advocates for environmental protection.

Today, Indigenous people are our neighbors, friends, and colleagues in our mountain community. Tribal nations continue to contribute to the cultural richness of the Durango area with their traditional music, dance, and arts. The tribes have also contributed to the region's economy through tourism, with many visitors coming to learn about the Indigenous cultures and history of the area.

Durango, Colorado, continues to be the home to several Indigenous communities, including the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the Apache Tribes, the Pueblo peoples, the Hopi Tribes, and the Navajo Nation. These community members, among other tribal members who have migrated to the area, have a rich history and culture. Undoubtedly, they have made significant contributions to the region throughout the centuries.

These tribes continue to play a central role in the Southwest and are valued members of the Durango community.